In the course of my research I've gone through a lot of parish records, and recently I found myself looking at the records for Abergwyngregyn, a little out of my area, but still of interest. Those making the entries in the Aber parish records seem to have been unusually diligent through the centuries, noting down numbers of deaths and even causes.

The Burying in Woollen Acts 1666–80 were acts brought in under Charles II and were ‘intended for the lessening the Importation of Linnen from beyond the Seas and the Encouragement of the Wollen and Paper Manufactures of this Kingdome’. Basically, it was to bolster up the wool trade at home in the United Kingdom, which was threatened by foreign imports and new fashions for linen or silk. The penalty for burying in cloths other than woollen was £5, a sum worth almost £600 today, or, in 1670, six stone of wool or 71 days wages for a skilled tradesman. The fact that, to be precise, £568.89 of today’s money would pay for 71 days of skilled labour in 1670 is fascinating, but a topic for another day. It does, however, show the difficulty of translating the worth of money from one time to another.

Incidentally, it seems that people who died of the plague were exempt from this law. I don’t know how much a woollen shroud would have cost, and how this law affected the poor, but it seemed that if one was too poor the burial entry could be marked ‘naked’. It’s stated here that rich people often ignored the law and paid the fine instead. A useful incentive for informing on those flouting the law was that half the fine was paid to the informant, and the rest to the poor.

I don’t know why the Caerhun and Llanbedr records escape

these annotations to affirm burying in woollen. It’s worth noting that the

entries themselves in the Aber records don’t seem to carry a note about being

buried in woollen, and the affidavits are on separate pages, so perhaps Caerhun

and Llanbedr did the same, and the affidavits have been either lost, or just

not included in the records I have access to.

An example of the Aber attestation, usually made by a relative, reads:

William Rowland of the parish of Aber in the County of Carnarvon made Oath that Rowland William of Aber & County of Carnrvon aforesd lately deceased was not put in wrapt or wound up, or buryed in any shirt shift sheet shrowd or any thing what soever, made or mingled wth flax hemp silke haire gold or silver, or in any stuffe or thing, other then what is made of sheep’s wool onely nor in any Coffin lined or faced wth any cloth, stuffe or any other thing whatsoever made or mingled wth flax, hemp, silke, haire, gold or silver or any other material by sheep’s wool onely: Dated the ffive & twentieth day of October in the Thirtieth yeare of the Reigne of our Sovereigne Lord Charles the second Kind of England, Scotland, France & Ireland &c Annog Doni 1678

Sealed & Subscribed by us who were present wittnesses to the swearing of the above said Affidavit

John Morris

Anne Pierce

It’s also signed by Richard Gruffith of Llanfair, Esq, justice of the peace.

How much this might have bolstered the wool trade is shown in the lists of deaths kept for the parish of Aber during this period. At one point a list is made of ‘the Burials in the Parish of Aber For 58 years’, between 1682 and 1744. The total, if I’ve added correctly, is 510, which is an average of just over 8 deaths a year. The highest figure in one year is 27 deaths. The caveat with this is some of the entries are noted as ‘besides children’, so the true figure may be higher.

Some of the later deaths have causes added in the margin, and Aber record keepers are quite diligent with this, off and on, right through into the twentieth century. Fever is very common in the entries around the eighteenth century, including ‘fever of the pleuritick kind’, ‘fever, nervous and malignant,’ and a ‘nervous fever wth a very bad & nearly malignant swelling in ye throat & scrotum very rife and epidemick, wch swelling carried off ye Malignancy for that year’. 1739 death causes listed include 6 infants, 1 astmha [asthma?] & dropsy, 1 consumption, and 1 feminine obstructions & dropsy. Other years mention consumption, ague, childbirth, palsy, diarrhea, decay, mortification in bowels, bloody flux taken at Leverpool, and old age. 1746 sees ‘died of a Dafadan wyllt [literally wild sheep] or canker in the Face & Throat’. Morris Owen was buried on 19th March, 1740 [1741] after ‘a lingring Diarrhea for several years & died of it at last abt 70 years old’. In 1742 two strangers died of ‘accidental & Sudden Death’, but no more details are given.

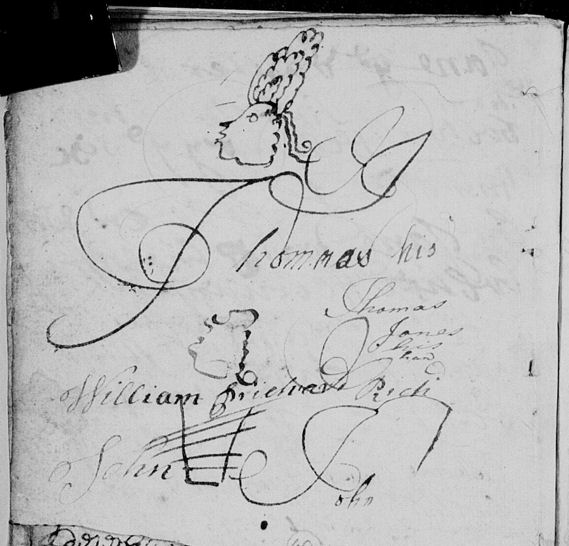

Amongst all of these grave and solemn entries an element of whimsy enters the records at points. It seems as if a child got hold of the book at some point, and made the most of the writing paper, alongside asides by adults, perhaps. Thus we find aphorisms such as ‘A Rich man Saddleth a poor mans back’ as well as ‘Hugh Wms his hand aged 10 years’ ‘Hugh Williams his hand AD 1748 ye October 2 aged ten years’. At one point the writer became more bold and wrote a crude rhyme:

Hogy pogy nasty swine

I draw for my valentine

but if you take it a punt

Pray rue you[r] choice and -

This last line has been crossed out, but beneath the smearing appears to read ‘shew your cunt’.

A crude rhyme.

There are also various doodles on the pages, a lovely human addition which, along with the other scribbles, show the fun and reality of those living in this time.

More serious would have been another entry from 1743, reading 'Margaret ye illegittimate & incestuous Daughter of Mr Stafford Wynne by his Own Niece Mrs Ann Wynne (his Brother’s Daughter) was baptiz’d – April 17th'. It's to be assumed that Stafford Wynne was a man of some standing, since he's accorded the title 'Mr'.

In 1730 another illegitimate birth is recorded: 'Joseph, the illegitimate Son of Joseph Hodson a Lancashire man & Anne Jones of Trefriw was born at Bodsilin (the mother being deliver’d there in her way to Anglesey as she pretended) & baptiz’d in ye Parish church of Aber Decr 27th 1730.' Why was Anne Jones, heavily pregnant, making her way from Trefriw to Anglesey, presumably over Bwlch y Ddeufaen? How did she meet Joseph Hodson, of Lancashire? Why add the words 'as she pretended', as if she may not have been intending to go to Anglesey after all?

The fatal Traeth Lafan (image by Reading Tom, on Flickr, used under CC BY 2.0 Deed)

Back to deaths, and this historical crossing place between the mainland and Anglesey can be seen in all of its danger. Traeth Lafan could have been used as a crossing place by the brave, while the tide was out, but was also probably used by locals picking shellfish. Entries involving this dangerous area include, in 1769, 'Hugh Evans of Llanbed [probably Llanbedr y Cennin], found drown’d in Lavan Sands, buried 30th October'; in 1797, 'William Lewis, and William Thomas two Mariners belonging to the Brig Sandwich of Amlwch, who were drowned on the Lavan Sands, and likewise Gwen Timothy, a Paſsenger on Board the same were buried. Octr 16th'; in 1817, '‘Three Unfortunate People drowned on the Lavan Sands April 21 1817. Ellen Roberts, Crymlyn, April 24th, age 56. Catherine Roberts, Crymlyn, April 24, aged 24. Sarah Williams, Crymlyn, April 26, aged 9.' It seems likely these would have been three generations of the same family, or a mother and two sisters far apart in age. A year later in 1818 there was 'Richard Hughes of Red Wharf whose Body was Discovered on the Lavan Sands, February 1st'; in 1819 there was 'November 12, a young Man unknown who was drowned on the Sands opposite to Beaumaris'.

Drownings were not confined to the sands. In 1722 the burial is recorded of Jane ’vch Sion Prees of Henfaes, who was drowned in Ogwen River. In 1767 William Morgan, 'a stranger', was buried, having been found drowned in Aber river. An alternative record describes him as 'Man that Drop down in the River January the 4 1767'. Other deaths, presumably not involving drowning, include a harper from the Alms House (1769), Jane William Probert, a butcher woman (1725), and a seven month old 'infant and stranger' who was 'found on Wellington Field' (1818).

Accidents caused a number of deaths, including Rowland Williams who fell from the shaft of a cart aged 23 in 1822; William Thomas, Ty’n y gerddi, ‘killed by the accidental Rolling of a Stone fro the Hill above Henffordd’ in 1825; Charlotte Kelly, 19, killed by the accidental discharge of a gun in 1826; Mary Griffith of Priddbwll, aged 50, burnt to death in 1862.

On 28th April, 1884, Elias Roberts of Cwrtiau,

aged 35, was buried, having fallen off the church tower at Penmaenmawr. The Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald for 2nd May is more forthcoming on this accident, telling us that Roberts was a stone-cutter working on the new tower being ercted at Penmaenmawr's St Seiriol's church. He suffered a scalp wound, spinal damage, and considerable bruising. He never regained consciousness, and died two days later. A single man, he was brought to his mother's home in Aber, from where he was buried.

The tower of St Seiriol's Church, Penmaenmawr (Photo by Meirion on Wikimedia, used under Creative Commons Attribution Share-alike license 2.0)

The building of the North Wales railway line brought a new kind of peril. This was built in the late 1840s to connect London to Holyhead, and so Dublin, and must have felt like a sea-change for life on the North Wales coast. The first death recorded in association with the railway was, tragically, a three and a half year old boy, Thomas Williams, of the Lon Pentre Du Crossing, who was ‘Knocked on the head by a passing Goods Train’ in 1875. This was followed by the death of Evan Jones of Bryn Gwylan in 1880.

In 1908 John Parry Jones of Henfaes Cottage, died aged 15, having jumped from a train. The Welsh Coast Pioneer and Review for North Cambria for 30th July tells us that the lad was a porter for the London and North-Western Railway Company, the son of a labourer. The train was scheduled to stop at Aber, but failed to make its stop. John Parry Jones opened the door and jumped out before others in the compartment realised what he was doing. One witness said that he seemed to hesitate for a second, and then slip. The communication cord was pulled but the train did not stop until it was near Tal y Bont, near Bangor, and no search was made for the victim. The inquest decided that he had been pulled from the train, travelling between 35-40 mph, by the suction of the wind, and 'a vote of sympathy was passed with the family.' The boy's body was not found until about half an hour after the accident, but it seems likely he would have died quickly, as 'one of the legs had been severed from the body. The right leg was cut off entirely above the knee, and he sustained other terrible injuries'.

Pentre Du Crossing was the locus for another series of interesting deaths with no clear explanation. The diligent record makers for Aber parish often noticed when the deceased were family, even with deaths some years apart, and the below list of siblings is rather fascinating for the young age of death with no other apparent connection.

1920: Gwyneth Roberts, Pentre Du Crossing, buried August 30th, aged 20

1929: Ceinwen Roberts, Pentre Du Crossing, October 21st, 1929, aged 21

1931: Emrys Charles Roberts, Pentre Du Crossing, May 28th, 1931, aged 20

1931: Eluned Roberts, Pentre Du Crossing, September 10th, 1931, aged 25

1932: Nellie Blodwen Jones, 3 Bron Cae, Llanfairfechan, buried January 6th, 1932, aged 34

1933: Menai Vaughan, Pentre Du Crossing, buried July 25th, 1933, aged 24.

It's unknown whether there was anything else to connect these sibling deaths, which must have been devastating for the family.

Other causes of death listed in the records include deaths on the mountain, and an outbreak of typhoid fever between 1866 and 1868 which killed nine in 1866, three in 1867, and two in 1868. Three people also died of cholera in 1866. Grace Rowlands died in 1829 of 'inflammation of the womb', aged 35. 1823 saw deaths from 'stone' and 'gravel'.